Introduction

In India, courts have gradually provided legal recognition of the intuitive fact that a public figure—having built his brand and fame through years of hard work—has the right to control over the use of his personality. Personality rights are simply a bundle of rights, usually falling within the broader scope of Intellectual Property Rights and IPR Law and within the narrow spectrum of copyright law. Personality rights are used in the context of a celebrity or public figure, which primarily include their privacy and publicity rights. While the former entails the right to be left alone amidst the following gaze of paparazzi, the right to publicity is the right to commercially control the use of own’s image and likeness.

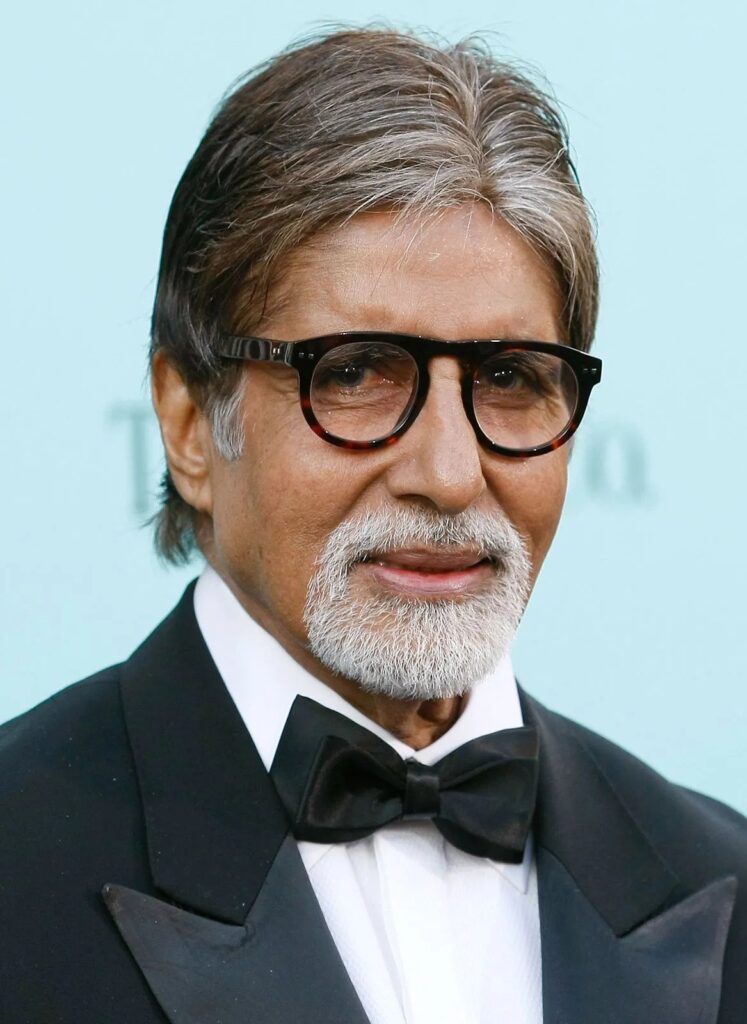

The Delhi High Court order from last year in the case of Amitabh Bachchan v. Rajat Nagi and Ors.[1] (“Amitabh Bachchan Case”) makes a remarkable development in the area of personality rights in India. The court in this case granted an ad interim in rem injunction against the unauthorised use of Amitabh Bachchan’s personality features such as his voice and images for commercial use. Passing an order against the named and unnamed defendants, this is the first time in India that a blanket John Doe order was granted for the protection of personality rights.

Brief Facts of the Case

Amitabh Bachchan (plaintiff) brought a suit against nine known defendants, along with unknown infringers (John Does/Ashok Kumars) for violation of his personality rights as a celebrity. It was alleged that the defendants were largely misappropriating aspects of his personality such as his photographs and voice to lure the public to use and/or download their mobile apps, websites and products. For instance, one defendant was using the plaintiff’s celebrity status to run a KBC Lotteries scam and another defendant sold t-shirts with the plaintiff’s photograph on his website.

The court found that the plaintiff was able to make out a good prima facie case in its favour and that the balance of convenience was also in his favour and against the defendants.[2] Finding that the plaintiff is “likely to suffer grave irreparable harm and injury of his reputation” through such unauthorised use, the Court granted an ad interim ex parte injunction against the named and unnamed defendants.[3] The court also directed the Department of Telecommunication and Union Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology requiring Internet Service Providers to remove the list of links and websites infringing the plaintiff’s personality rights and ordered telecom service providers to block all contact numbers used to circulate messages through WhatsApp which infringed the plaintiff’s rights.[4]

Personality Rights in India

There’s absence of an explicit recognition of personality rights in the statutes in India. However, certain aspects of a person’s identity and handwork are protected against commercial misappropriation through the Copyrights Act, 1957 and the Trademark Act, 1999. While such statutes can protect a performer’s rights (covered under copyright law) or a person’s name (under trademark law), the characteristics such as voice or the way someone whistles, or any other specific popular quirk of a celebrity cannot be granted protection. The value of, and right over, such aspects of the personality of an identifiable person has been recognised by the concept of personality rights.

Personality rights in India have been recognised and gradually developed by the courts through reliance on common law and jurisprudence in the US. Yet, the jurisprudence has been ambiguous and inconsistent in parts.

The courts have been on a consensus that the right of publicity vests in an individual (and not an event or organisation) and that he alone is entitled to profit from it. Such an individual is a public figure or a celebrity, which in the Titan Industries Ltd. v. Ramkumar Jewellers case (“Titan Industries case”) were defined as “a famous or a well-known person… who many people talk about or know about”.[5]

In the Titan Industries case, the Delhi High Court had noted a violation of the publicity rights of Amitabh and Jaya Bachchan by unauthorised use. In the case, Titan’s Tanishq (plaintiff) had signed an “Agreement of Services” with Amitabh and Jaya Bachchan for endorsement of their brand which gave them exclusive ownership rights of copyright over material pursuant to the agreement. However, the advertisements were used by third parties and the plaintiff brought an action for violation of publicity rights on behalf of Amitabh and Jaya Bachchan.

In the same case, court laid down two basic elements comprising the liability for infringement of the right of publicity:

“Validity: The plaintiff owns an enforceable right in the identity or persona of a human being.

Identifiability: The Celebrity must be identifiable from defendant’s unauthorized use.”

Even in the Amitabh Bachchan Case, the test was applied and implies that a certain degree of popularity and fame is required to enforce the right.

It is unclear whether the element of confusion in the minds of the public has to be proven. While the Titan Industries Case provides that the “falsity, confusion, or deception” is not essential to be proven in a claim of publicity right infringement, many other judgements have followed an approach wherein they tested whether misconception was created in the minds of the public by use of the personality features, akin to the test of passing off. In juxtaposition to this association of publicity rights with trademark and the passing off by several judgements, the ICC Development (International) Ltd. v. Arvee Enterprises and Anr.,[6] (“ICC Development Case”) and the separate opinion of Justice SK Kaul in KS Puttuswamy v. Union of India[7] associated publicity rights to the right of privacy, which is a part of Article 21.

Therefore, despite the recognition of the concept of publicity rights in the early 2000s in the ICC Development Case, the jurisprudence on personality rights in India remains plagued with contradictions and confusion decades even after it. Although interim orders are generally precise and follow a standard form, it was expected that the order in the Amitabh Bachchan Case lay down the rationale behind the decision or mention the theoretical basis of the publicity rights to provide clarity—especially since the law on the subject remains vague.

The Impact of the Amitabh Bachchan v. Rajat Nagi and Ors. Case

The grant of a blanket restriction against commercial exploitation of the plaintiff’s celebrity status indisputably is a step in the direction of strengthening the right to publicity. If this relief is given by the courts in future cases as well, it will effectively take off the burden from the plaintiffs to identify all the infringing defendants in a suit to restrain them. This is especially helpful in cases where mass unauthorised use of a person’s photograph, voice, etc. takes place.

However, such a John Doe injunction order also raises questions on the interplay of publicity rights with Article 19(1)(a). As noted by the Delhi High Court in DM. Entertainment Pvt. Ltd. v. Baby Gift House,[8]“in a free and democratic society, where every individual’s right to free speech is assured, the over emphasis on a famous person’s publicity rights can tend to chill the exercise of such invaluable democratic right.” With this observation, the court carved out an exception with respect to caricature, lampooning, parodies and the like.[9] Whether the John Doe in the Amitabh Bachchan Case order applies to such categories of expression remains unclear.

Further, going forward, there could be a conflict of publicity rights with the right to livelihood as well. Various small local shops and businesses in the country use celebrity photographs outside their shops to attract customers or sell products with their photographs. Yet, a common man is unlikely to be deceived that such local shops are endorsed by the celebrities themselves. There’s uncertainty regarding the applicability of such injunctions on small-scale shops and businesses.

The balancing exercise that would need to be performed in light of the abovementioned conundrums requires for the courts to settle whether publicity rights can be placed as a fundamental right due to association with the right to privacy, or whether they can be traced in any statute or lie in the realm of torts.

Therefore, while an ad interim in rem injunction is beneficial for the plaintiff, a permanent John Doe injunction can be harmful given the contradictions which exist in the law of publicity rights.

By Khushi Singh, Intern

Footnotes:

Footnote [1] 2022 SCC OnLine Del 4110.

Footnote [2] Id.

Footnote [3] Id.

Footnote [5] 2012 SCC OnLine Del 2382.

Footnote [6] 2003 (26) PTC 245.